Many persons live their entire lives without ever seeing a human being die.

Howard Thurman, “Life Must Be Experienced” in The Inward Journey

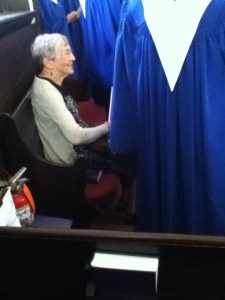

At the time, I didn’t realize what a privilege it was to sit with my mother and then my father as they passed from one life into the next.

In some ways, it felt like an awfulness. Especially with my mother, with that gurgle of excess fluid that the nurse would suction out to make her more comfortable. It’s a sound I won’t forget.

And I prayed in my mother’s last few days conflicting prayers of “Please, Lord, let her live until my sister gets here” and “Please, Lord, relieve this terrible suffering.”

She lived until my sister arrived. We were all gathered around my mother’s bed in the hospital — her living children and my father — as she died.

My father went more quickly. One day he was up, dressing himself, coming out breakfast. Before the end of the day, my children had to help him back to bed. The next day he didn’t get out of it and he died that evening.

My brothers were there. One sister-in-law. One nephew. Most of my children. His home health aide. My sister had not yet arrived. My brother played a song on a CD for him as he passed.

My sister got there in the wee hours of the morning and went to see him as he was laid out in his bed. The hospice nurse who had prepared the body had clasped my father’s hands across his abdomen and it looked so unnatural. He looked so dead, and I wished with all my heart that my sister could have seen him alive one last time. We had Face-timed with her in the afternoon, but it’s not the same.

These days, the stories that come out of the hospitals impacted with COVID are awful — the shortages of rooms, equipment, and personnel. The makeshift morgues. The isolation.

I wept one day in the car listening on the radio to a nurse describe staying over and over after her shift had ended to sit with a dying patient because she didn’t want anyone to die alone. How many patients had she done that with? I don’t remember — but it was many.

And I realized the great privilege I had — to sit with my parents in a non-COVID world and tell them I loved them one last time.

![IMG_3634[1]](https://28daysatatime.files.wordpress.com/2014/05/img_36341.jpg?w=225)