The paper fluttered out of my Bible one morning.

I had written the following quote on it:

You may choose to look the other way, but you can never say again that you did not know.

William Wilberforce

William Wilberforce spoke those words to Parliament in 1789 as he told of the horrors of the slave trade.

The quote fit perfectly with the book I was reading, The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas. My friend Shannon had recommended it, and midway through she asked what I thought of it.

“It’s a brutal view into a world that I don’t know,” I told her.

And it is.

I grew up in a white town, attended a white school, had white friends. There’s nothing intentionally racist about that; it’s just a fact. Small upstate New York towns were predominantly white in the 60s and 70s.

At my father’s birthday party, a woman, while looking at one of his old yearbooks, said to me, “This is fascinating.”

“What?” I asked.

“His high school had two choirs — one white, one black,” she said.

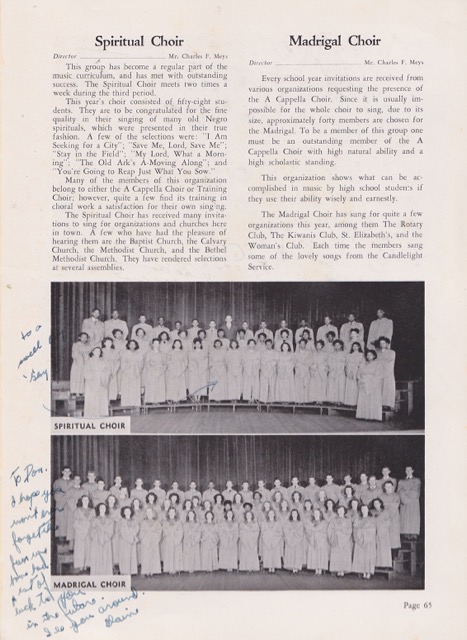

I looked at the yearbook — the 1947 Cobbonian from Morristown High School. One page did feature two choirs: the Spiritual Choir and the Madrigal Choir.

The reverse side of the page featured the A Cappella Choir and the Training Choir, both of which were integrated — just barely — with less than a handful of people of color participating in either one.

“We’ve come a long way, haven’t we,” I said to the woman looking at the yearbook. She smiled and nodded.

But we still have a long way to go.

For the breadth of Angie Thomas’s book, I was allowed to stand in the shoes of a 16 year-old African-American girl, who grew up in the projects, who saw two friends gunned down, and who ultimately learned that her voice is her most powerful weapon.

I thought about the book this weekend when I saw the news coverage of students across the country participating in March for Our Lives Rallies against gun violence. They used words — and silence (after reading the names of the 17 students who died at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High, student Emma Gonzalez stood in silence on the stage for 6 minutes and 20 seconds, the amount of time it took the gunman to kill them).

I’ve read solutions to the gun problem that range from arming teachers, to supplying buckets of rocks in classrooms, to having therapy dogs in schools. Some sound disastrous; others seems inefficient and ridiculous; still others might work. I don’t know what the answer is —

But I do know it begins with talking and listening.

It begins with standing in the other person’s shoes, no matter what the issue is, if only for a moment.

After that, I can choose to look the other way.

But I can’t say I didn’t know.

I’m glad I read The Hate U Give.

Yesterday we had a guest preacher, a woman from a nearby city. When she called the children forward for the children’s sermon, two school-age boys and one toddler girl came forward.

Yesterday we had a guest preacher, a woman from a nearby city. When she called the children forward for the children’s sermon, two school-age boys and one toddler girl came forward.

I walked last night as if in a dream. It was a moonless night and I had not brought a lantern. As I passed the open doors of the Chenango House, light streamed out. I could hear laughter and music within. Once passed, I walked in darkness and all I could hear was the flowing water of the Chenango River. It beckoned me, like the Icarian Sea.

I walked last night as if in a dream. It was a moonless night and I had not brought a lantern. As I passed the open doors of the Chenango House, light streamed out. I could hear laughter and music within. Once passed, I walked in darkness and all I could hear was the flowing water of the Chenango River. It beckoned me, like the Icarian Sea.