“Are you feeling better?” my father asked me Monday morning.

“What do you mean?” I asked.

He looked at me, perplexed. “You’ve been sick,” he said.

I laughed. “No, Dad, I’ve been in Nashville at that conference I go to every year.”

“When I didn’t see you,” he replied, “I thought you must be sick and in the hospital.”

His world consists of a failing mind and body. To explain my absence, he made up a story that fit his world.

While I was in Nashville, I didn’t read the news. Not a once. For four whole days.

No news may not be good news, but sometimes it’s just good.

Oh — I thought about it. People talked about it. The news felt like a rip current that threatened to pull us under and drown us in our differing opinions.

But at Hutchmoot, grace, tenderness, and humility surrounded us like a warm blanket. Our commonalities pulled us close and the day’s political controversies didn’t drive us apart. In fact, when, one evening at Hutchmoot, that rip current threatened in a particularly diabolical way, Andrew Peterson, our proprietor and host, showed us how to handle even the most treacherous waters — reaching out like the very best of lifeguards to pull us to safety.

The Brett Kavanaugh – Christine Blasey Ford controversy is mostly over, ending while I was away. It was an earthquake followed by a tsunami — and now America moves on – battered, skeptical, self-protective, and uglified by debris.

I couldn’t help thinking about how my father truly believed his own story of me being in the hospital. It fit his world.

And I daresay people who could insert themselves into Christine Blasey Ford’s story, who knew what it was to be sexually assaulted, found themselves making their story her story. Perhaps they remembered how they couldn’t tell anybody because of the shame they felt. Perhaps they remembered how they wanted to move far far away and start over in a new place without the reminders of that terrible act.

On the other side, people who had been falsely accused, who had been doing their best to do their best, working hard and keeping their nose clean for decades, who suddenly had been falsely blindsided by some incident from 30 years ago — perhaps they watched Brett Kavanaugh and asked themselves, how would I handle this? Perhaps, they told themselves, This is so unfair. Perhaps they know that they, too, would have gotten a little testy under that questioning.

But we don’t take the time to stand in someone else’s shoes. We put them in our story and force it into a narrative that may or may not be true. We make it make sense in a way that makes sense to us.

Like my father putting me in the hospital.

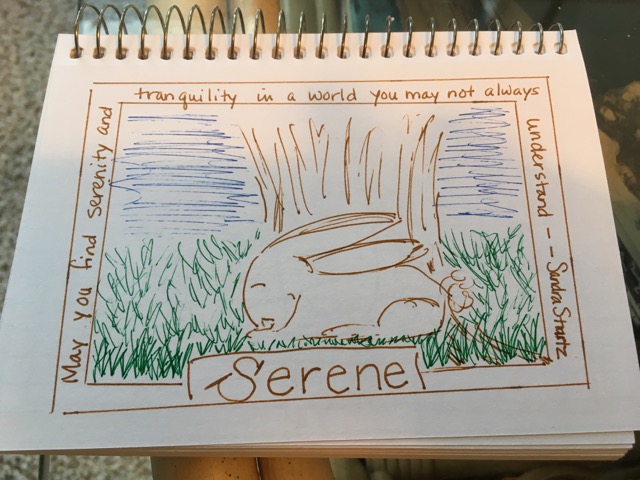

At Hutchmoot, I found a tranquil haven from the current current-news storm.

Thinking ahead to the next storm and the next — because we seem to be in a political hurricane season in the US — I’m going to try to do more listening, less trying to inject my assumptions into the news stories. More trying to understand the fraught emotions on both sides, less knee-jerk judgmentalism. More compassion, more looking for common ground.

I would rather be a safe haven than a whitecap on this stormy sea.